ISIS lives off bare bestiality. While their opponents are paralyzed with fear, the work of satirists flourishes. Meanwhile Bashar al-Assad tries to present himself as the lesser evil in Syria.

“Daesh – May their ‘glory’ be of short duration” – Syrian intellectual Yassin Al Haj Saleh exclaims in the documentary “Our Terrible Country”, sarcastically imitating the presumptuous and threatening connotation of ISIS’ own statements. “Daesh,” he remarks on another occasion, “That sounds like a monster from those fairy tales we were told as kids.”

The monstrosity of ISIS exceeds that of any mythical creature in many respects. Materially, ISIS benefits from numerous sources – financiers were attracted, even though the Gulf States deny any responsibility; protection money extorted from businesspeople, ransoms for hostages, goods captured in the course of conquests, from money and weapons to oil – preferentially sold to the Syrian regime – secure its survival.

Ideally, ISIS lives off bare bestiality. It allows for them to recruit among those who feel deprived of their rights and who believe that fighting for ISIS, for the first time, allows them to feel superior and to exert power, without having to assume any responsibility or obey any rules. As a result, their opponents are paralyzed with fear or driven into flight: “I have experienced many horrible things, but my fear was never greater than in the moment I saw ISIS descend on a place. Masked gunmen who, without hesitation, demonstrate their power in a brutal manner – that caused more horror than anything that had happened before,” a female activist says.

There is a tool with which Arab activists and media representatives tackle them: the work of satirists flourishes despite or perhaps precisely because of the serious threat through ISIS. Anthony al Ghosseini, for instance, mocks them by claiming that ISIS did not choose Lebanon as a target because it simply would not know whom to overthrow here. He assumes that the country’s traffic problems would also complicate an advance on Beirut.

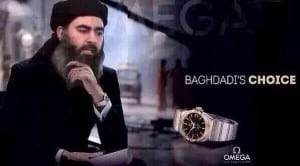

The sight of “the caliph” wearing an expensive western watch attracted a great deal of ridicule on Twitter: “#Baghdadi’s Choice- from #Omega… available at all #ISIS-Stores in #Syria and #Iraq,” reads a tweet by @AL_Khatteeb. Its prominence measures up to the incident where extremist leader Zahran Alloush was spotted using his pink Hello Kitty notebook.

ISIS is aware of the value of a public staging of brutality. Unlike many other brutes who attempt to sell themselves as the “actual good guys” who practice violence only because they are forced to do so, ISIS makes a point of placing their atrociousness in the centre of attention.

Who cares about 11.000 tortured Syrian people?

That easily makes them everyone’s enemy. To be in opposition to ISIS is a matter of course, which means no government can afford to remain silent when it comes to ISIS. That this does not necessarily have to be followed up with actions is best portrayed by the Syrian regime. From the very beginning, it has showcased reluctance when considering an attack on ISIS. This terrorist militia is an opportunity for Assad to present himself as the lesser evil. As far as domestic policy is concerned, it is at the core of Assad propaganda to not resemble a normal ruling family, but to decorate themselves with godlike attributes: “Assad for eternity” and “Our eternal leader, Assad” are merely two examples of the slogans that were insistently painted on city walls and posters for 40 years. Placards with the portraits of Hafez al-Assad, Bashar and his late brother Basel together were at times even compared to the depiction of the Holy Trinity, “Father, Son and Holy Ghost”.

From a personality cult driven into heavenly spheres in Syria and a hopeful idealization of the dictator as the guardian of minorities and a secular stronghold against extremism, it is a long way to measure the regime’s actual infernal dimension. There is no shortage of YouTube videos of regime henchmen who have filmed themselves torturing and murdering prisoners. The 55,000 images of 11,000 people tortured to death in Assad’s prisons – pictures taken on behalf of the regime and later smuggled abroad – are seemingly easier to brush aside. Unlike in the ISIS videos of decapitations, it does not explicitly say that they were a message addressed to the U.S. or the West, so why should they be understood?

At an international level ISIS elicits blind activism, which, up to this point in time, is limited to half-baked military strategies which lack adequate political substantiation. Air strikes against ISIS are a start, however the circumstance that there is no active debate on a vehement advancement against Assad and that he is even seen as a potential partner in some circles causes resentment. This, in turn, is met with a lack of understanding in the West. “Now we’re doing something and you’re still not happy,” such is the reasoning often voiced. However, many Syrians view Assad and ISIS as two guises of one and the same despotic and inhuman spirit, and even believe that they, in some respects, resemble each other in every detail: “You know when I arrived in Raqqa and saw the new slogans mounted by ISIS, I had to look twice,” an artist tells us. “The writing originated from one and the same calligrapher.”

Palestinian satire on ISIS, Al-Filistiniya TV, June 29, 2014 [via MEMRI].

Whilst ISIS’ attitude at an international level attests to megalomania, its own naming is characterised by pettiness. Not only do they want to be known as the “Islamic State of Iraq and Syria” (or Levant), as it displays that the pre-colonial, uniformly labelled entity they would like to invoke never existed. They wish to appear as the Islamic state per se. Their grandeur is not meant to be belittled or made into a random part of the alphabet soup. That is why the use of the Arabic acronym “Daesh” („al-Dawla al-Islamiya fi al-Iraq wa al-Sham“) is no joke. They punish the profane habit of using abbreviations with draconic measures. The fact that “dawla” (state) is also a modern term that has little to do with a historical caliphate is irrelevant.

In this state of general perplexity as to how best to deal with ISIS – not to mention a political solution that could pacify the region – even rhetorical straws are grasped at. In France, for example, the attempt is being made to call ISIS neither ISIS nor IS, but rather “Daesh”, a term despised by extremists. French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius remarked: “This is a terrorist group and not a state. I do not recommend using the term Islamic State because it blurs the lines between Islam, Muslims and Islamists. The Arabs call it ‘Daesh’ and I will be calling them the ‘Daesh cutthroats.’”

This article was published on October 21, 2014 on the English website of Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. The author, Bente Scheller, is a German political scientist who has been extensively working and researching on Syria. Since 2012, she has been the director of the Beirut office of Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. In 2014, her book called “The Wisdom of Syria’s Waiting Game: Foreign Policy Under the Assads” was published. We republished this article using the Creative Commons license.